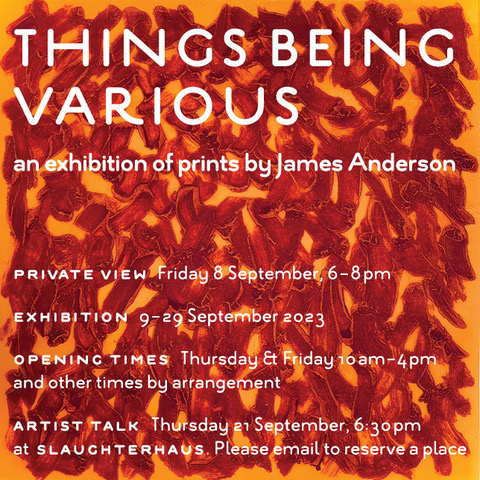

JAMES ANDERSON’S new exhibition (from 9-29 September) is called “Things being Various”. Like his previous one, it is named after a line from a poem – Snow by Louis MacNeice. The poem evokes the suddenness of the poet’s realisation of the contrasts and diversity and plurality of the life around him; of life itself:

“World is crazier and more of it than we think, …incorrigibly plural …The drunkenness of things being various.”

James’ work – large, painterly, colour-dense carborundum abstracts, delicate etchings and graphic, layered wood-cuts – suggest a very literal expression of “things being various”. But the joy of the show is not (simply) in this display of printmaking craft, it is in the artist’s ability to tease out a scatter of moods and images that visualise a world within: his world. These are works that seem to capture the most fleeting of inspirations – the colours of the Atlas mountains, a view seen through the inside of a friend’s house, the fall of a shadow under a tree – interpreted through the solidity of print.

MacNeice’s poem begins with the words, “The room was suddenly rich”, and there’s a sense of that suddenness, that ephemeral shock of memory/joy/excitement/drama in much of the work. James’ strength is his ability to create images that reflect that suddenness; they feel as though they’d just burst into his consciousness; the prints shout, “see what I see, feel what I feel”. He has the craftsman’s ability to work with, and create work, born of the studied carefulness of printmaking (layer upon layer of ink and chine-colle paper and acid eating into metal and hard steel gouging into slabs of wood) that has been coaxed to yield rich emotional immediacy.

James has said that it was only after his introduction to printmaking that his innate creative sensibility was able to express itself; that, as he puts it, “the possibility of art could exist”. He is an artist for whom the idea and its execution are so closely interlinked that one could not exist without the other or to retreat to an old cliche, “the medium is the message”.

And herein lies the tension that electrifies all his work: the synaptic spark of ideas. The work is grounded in the cerebral, philosophical truths of a poem (akin to Gombrich’s reference to “the possibility of metaphor [in art]”). And at the same time, as the visual reality of the work– the “ocular truth” – suggests, it is effortlessly free, “lively” (his word) and expressionistic.

In his inner world, of things being various, the cerebral is merged with the celebratory.

Lee Johnson